A Stitch

In Time

A History of New York’s Fashion District

A publication of the Fashion Center Business Improvement District

Written by Gabriel Montero

Download a pdf of this publication.

The Fashion District has been synonymous with design since its inception in 1919, and today it is still the living center of American fashion design, home to the greatest concentration of fashion designers in the country. But beneath the gloss of fashion lies a rich history of the people who gave life to this colorful and enduring New York neighborhood.

Fashion was not always the neighborhood’s claim to fame. Instead, the area now known as the Fashion District was once the most infamous neighborhood in the country, a playground of squalor and vice known as the Tenderloin and the Devil’s Arcade. It was home to the largest concentration of prostitution the nation had ever seen, and along with that came a teeming underworld of bootlegging, betting and racketeering.

The illegal sex trade was originally drawn to the area because of the explosion of theater-building that occurred there between 1870 and 1900. Hotels, casinos and a thriving nightlife soon followed. As life on the street got to be too boisterous for the wealthy landowners who inhabited the Tenderloin’s side streets, their properties were rented to the only residents who were willing and able to pay rents in the rapidly-emptying area: high-class prostitutes. As late as 1919, the highest concentration of arrests for prostitution in the city was still to be found in the district.1 In fact, the district was named the Tenderloin by the local police captain, Alexander Williams. When asked what he thought of his recent assignment to the area, Williams famously answered, “I like it just fine. I have had chuck for a long time, and now I intend to eat tenderloin.” Many thought this was a reference to his belief that corruption in the area would prove lucrative for him, but Williams took to cracking down on the area’s vices with a certain relish, eventually earning the nicknames “The Clubber” and the “Czar of the Tenderloin.” But the truth is that not Williams, nor the many other police captains, priests and social reformers who tried, could stop the sex trade from flourishing there – even after decades of trying. At the dawn of the 20th century, the question on the minds of many was: “Who or what could possibly reform the Tenderloin?” No one would have dreamed the garment industry would be the answer to that question.

Birth of the

Garment

District

The Tenderloin became the Garment District when hundreds of thousands of immigrant garment workers were “pushed” into the area, and effectively quarantined, by the powerful Fifth Avenue Association, a group comprised of some of the country’s wealthiest and most influential citizens, who were of one purpose: to rid Fifth Avenue of industry and its unpleasant by-products, namely its immigrant workers.

The creation of the Garment District is one of the most important events

in the history of American urban planning and politics, and one that has had enormous consequences for the shape of New York City today.

Workers and developers found in the district a site where they would carve out their own distinct destiny – as immigrants, as workers and as citizens of the city. They did this through the formation of unions, through new forms of architecture and through a unique urban culture unlike anything seen before. Their struggle to shape that destiny is not simply a story of struggle to create a home for American fashion. It is also a story of workers and immigrants who fought for their place in a city that seemed, at times, not to want them. It is among the most important stories in New York’s ongoing struggle to define itself.

Between 1828 and 1858, the garment industry grew faster than any other industry, aided by the invention of the sewing machine. Prior to that, New York served as the nation’s largest site for textile storage, so it was only natural that the production of clothing should also take place there. When mass-produced uniforms were needed during the Civil War, the government turned to manufacturers in New York City.

By the early 20th century, the majority of immigrants who worked in the industry were Eastern European Jews. As Jews in Eastern Europe at the end of the 19th century could not own land, the majority were forced to live in cities, where they were compelled to learn skills applicable to industrial life, such as manufacturing, commerce and textile production. In fact, of all immigrant groups arriving in the United States between 1899 and 1910, Jews had the highest proportion of skilled workers, at sixty-seven percent. More importantly, one-sixth of the Jewish workforce in Russia was involved in clothing manufacturing, over 250,000 workers.2 At the time of their emigration, the skills of Eastern European Jews perfectly matched the industrial landscape that was taking shape in New York. In fact, the garment industry during that period employed roughly half of all the city’s Jewish males and nearly two-thirds of all Jewish wage-earners.3 And, as a whole, by 1910, the garment industry incorporated around forty-six percent of the industrial labor force in the city.

At the end of the 19th century, garment production was done at home, often by entire families, including children. Because it was done at home, it was not subject to regulations, with the consequence that sanitation lapsed and exploitation was rife. The apparel trade was centered in the Lower East Side, a neighborhood marked by poverty and extreme overcrowding. Hundreds of thousands of Jewish immigrants found their way to the Lower East Side’s so-called dumbbell apartments. Named for the shape of their layouts, these apartments lacked public toilets, adequate light and ventilation.

Loft Factory

& Triangle

Shirtwaist

Factory Fire

Concerns about health and safety, particularly the spreading of smallpox through clothes made in vermin-infested quarters, sparked legislation that effectively brought to a close the tenement system of production. The State Factory Investigating Commission Report of 1911 recommended the complete abolition of tenement work. Spurred on by these health concerns, the garment industry would enter a new phase with a new type of production facility: the loft factory. The new building form promised to provide the light and air that had been sorely lacking in the tenements, thereby providing better working conditions. Unfortunately, history has shown that they invited instead a new set of exploitative practices, such as following workers around to prevent idling, covering clocks and locking doors to prevent early exiting. In fact, it was the latter that resulted in one of the most infamous industrial disasters in American history: the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire. In that great tragedy, 146 workers lost their lives when the factory’s doors were locked from the outside to prevent workers from leaving.

The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory was known to employ around 600 workers, spread over the top three floors of a loft building on Greene Street, near Washington Square. Almost all the workers were young women between the ages of 13 and 23, mostly of Jewish and Italian descent. Sometime around five in the afternoon on March 25, 1911, a fire

started on one of the cutting tables on the eighth floor. Flames soon engulfed the entire structure because, despite its stone facade, the frame interiors of such “modern” lofts were made of wood and burned easily. As the fire spread and workers and managers scrambled to try to put it out, they seemed almost inexorably ushered toward their doom.

The fire hoses that were pulled from the stairwells did not have any pressure or water and therefore proved useless. Hundreds of workers ran to the exit doors but found them locked, bolted from the outside to prevent early exiting by the workers. Those who could tried to pile into the elevators; many were crushed as workers frantically piled on top of one another. In many instances, only those who were literally strong enough to fight for their place were able to ride the elevators to safety. Others jumped to their deaths from windows in order to escape the flames.

All told, 146 workers died that day, their bodies overwhelming the ambulances that arrived at the scene. Any merchant with a pushcart or a wagon tried to help load bodies and take them to makeshift morgues established in nearby stores.

Indeed, conditions in the garment lofts were generally deplorable. Workers were promised pay that was rarely given and had deducted from their wage the cost of the electricity required to operate their machines. Women, in particular, faced an even more pernicious “tax” while working: harassment, often of a sexual nature. In fact, the birth of the first successful garment union, the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU), led by women, can be traced back to the Triangle Factory, where, prior to the disaster, female workers were harassed, and then fired, for joining a union. The ensuing strike in 1909 became known as the Uprising of the 20,000 and marked the start of the modern garment labor movement. The Triangle Factory was, therefore, at the center of the industry’s efforts to reform itself, for in the wake of the Uprising and the Fire, new laws were passed to improve working conditions and prevent disaster.

Fifth

Avenue

Association

By around 1915, the loft and the industry were on their way to being rehabilitated. Just then, however, the industry ran into an obstacle that would change the course of its history: too many lofts, and too many “undesirable” garment workers, had started to encroach on Fifth Avenue, then considered the most expensive and exclusive stretch of real estate in the entire nation.

Between 1900 and 1910, the number of garment workers employed near Fifth Avenue nearly doubled. Not only were lofts cheap to build, but the industry preferred to be located near the great retail stores, many of which were arrayed along Fifth Avenue.

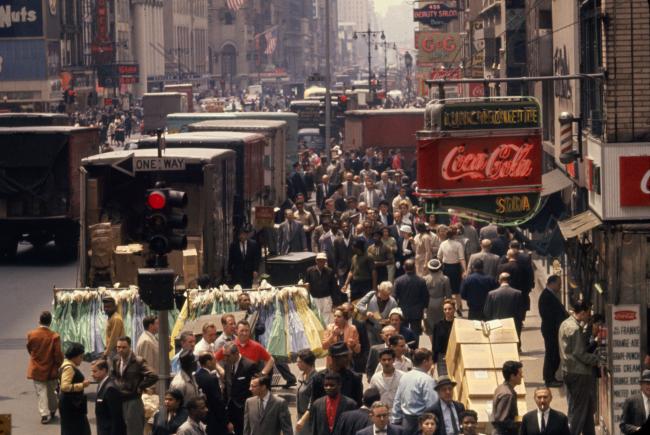

At the opening of the 20th century, tens of thousands of garment workers began to clog the streets of Fifth Avenue, strolling and window-shopping, and meeting informally to discuss the vagaries of the trade. For property and business owners along Fifth Avenue, however, the workers constituted nothing short of an immigrant horde that had to be stopped. One man above all worked to remove the garment trade: Robert Grier Cooke, founder and president of the Fifth Avenue Association (FAA). Right around the time of the garment loft explosion, Cooke had announced ambitious plans to transform Fifth Avenue into a thoroughfare that would compare with “London’s Bond Street…the Rue de la Paix of Paris…or the Unter den Linden of Berlin.” When it was completed, the avenue would see the elimination of cars and advertisements on buildings, the installation of “islands of safety” and a lighting scheme that would make “the Great White Way a downtown side street by comparison.” Farther uptown, argued Cooke, Fifth Avenue held out the promise of gathering together “all the beautiful architecture of the city which is as yet unexpressed.” Clearly his plans were jeopardized by the garment industry, which he saw as the single greatest threat to the existence of Fifth Avenue.

In its efforts to rid the area of garment workers, the Fifth Avenue Association used boycotts and even pressured large lending institutions to refuse loans for construction of new lofts. More importantly, throughout 1915 and 1916, the FAA worked tirelessly to pass a zoning law to keep garment lofts from entering the area as part of its “Save New York” campaign.

On July 25, 1916, the zoning law was passed, the first of its kind in the country. An editorial in the New York Times proclaimed it “the most important step in the development of New York City since the construction of the subways.” By October of that same year, ninety-five percent of garment manufacturers in the area around Fifth Avenue had decided to relocate.

A New Home for the Garment Industry

Troubles followed the garment workers. Everywhere they went, it seemed, they faced the same hostility. Instead of a boundary to keep garment workers out, the city leadership and the FAA decided that what was needed was a district where such workers could be segregated. In effect, such a manufacturing zone would serve as the urban planning equivalent of a quarantine.

The area finally settled upon was between 9th Avenue and Broadway and bounded by 34th Street and 42nd Street. The area was the heart of the Tenderloin district. Seizing upon the opportunity, real-estate developers, some of them former garment workers, formed a cooperative with the aim of transforming the Tenderloin into an inspiring industrial area, a city within the city.

The first new buildings, called the Co-Operative Garment Center Buildings, were built in 1920 at 494 and 500 Seventh Avenue, and were designed to wrap around two existing hotels, the Hotel Navarre and the Hotel York. As more and more land was bought up, the brownstones that once housed illegal bordellos were replaced with garment lofts, and the theaters and nightlife soon disappeared from the scene. In fact, by the end of 1919, prostitution had virtually been eradicated in the former Tenderloin. What the police and social reformers of the 19th century had failed to do, the garment industry accomplished in short order. By 1926, the Garment District was the fastest growing site of construction in the entire city.

Of the men who built these buildings and fueled the original prosperity of the district, three individuals must be singled out: A.E. Lefcourt, Louis Adler and Ely Jacques Kahn. A.E. Lefcourt was born on the Lower East Side, and began his career as a newsboy, saving enough money from his sales to start a bootblack stand on Grand Street. He eventually got a job at a dry goods store but kept his newspaper route and shoeshine operation by hiring others to run them. Lefcourt would go on to build some twenty buildings in the district, including the 34th Street Post Office. However, no building purchase held as much significance for him as the Hotel Normandie, on the corner of Broadway and 38th Street, which he purchased in 1929. It was in front of that hotel that Lefcourt had sold his newspapers as a boy.

Another of the pioneers who developed the district was Louis Adler, who came to the United States in 1895 as a boy and began working as a clerk in a garment firm. Like Lefcourt, he worked his way up through the ranks to become the owner of his own manufacturing company, before turning to real estate. Along with his partner, Abe Adelson, who also got his start in the garment industry, Adler built what became the district’s premiere fashion buildings at 530 and 550 Seventh Avenue.

Increasing land values and limited space meant that builders in Manhattan had to look vertically. But this required a new architectural style, for the only things to catch the eye from such heights were light and shadow. The architect Ely Jacques Kahn seized upon this challenge. Kahn became the principal architect of the district and one of the most important 20th century American architects.

Born in New York in 1884, Kahn studied architecture in Europe, but found himself, upon his return, largely closed off from the insular world of family-run architecture firms that required social position for entrance. Nevertheless, Kahn was determined to be a self-made architect, and this determination would stand him in good stead with the self-made men who were developing the Garment District.

Kahn saw in the skyscraper the natural tendency of built forms to “slough off” the bonds of ornamentation as they reached higher into the sky. What mattered now was that the office block create its own aesthetic sensations, a play of light and dark, “void and solid,” brought about by the architect’s sequence of planes.

Kahn saw this new style, this New York architecture, as “essentially American.” In building after building, some thirty between 1924 and 1931, Kahn set himself the task of creating a new vocabulary of forms using these austere and experimental principles. Indeed, it was Kahn who fashioned for the loft, and for the immigrant workers that it housed, a symbol that they had truly arrived and found a home on the American scene.

Kahn would eventually design ten buildings in the Garment District, the first being the Arsenal Building on Seventh Avenue at 35th Street. One of the last buildings that Kahn designed for the district, at 1400 Broadway, was built on the site of the Knickerbocker Theatre, a former landmark in the Times Square Theatre District that opened in 1893. In fact, the Knickerbocker was one of the many theatres that originally attracted prostitution to the old Tenderloin district.

With Kahn’s creations, not only had the former Tenderloin district been transformed and the garment industry given a respectable home, but the neighborhood even became the vanguard of economic and architectural development in the city.

World

Capital of

Fashion

It wasn’t until World War II, however, with the German occupation of Paris, that New York’s garment district became a vanguard of a different type: the world capitol of fashion. Facing wartime recession, and aware that the garment industry was the city’s single largest employer, Mayor LaGuardia was anxious to see the city take advantage of Paris’s demise to ensure its own ascent. Members of the industry and the garment union, along with Mayor LaGuardia, banded together to create the New York Dress Institute, whose mission was to promote the city as the premier site for fashion design and to bolster production and sales. “New York Creation” labels, depicting an iconic New York skyscraper, were to be stitched into all dresses made in the area. It was during this time also, in 1944, that the Fashion Institute of Technology and Design was created as a two-year college and was sponsored by the Education Foundation for the Apparel Industry of New York.

The cooperation between the union and manufacturers required for the Dress Institute was unprecedented, and was due in part to their common goal of promoting the city as a fashion capitol and in part to the maturation of labor relations. To kick-off the Institute, the labor establishment and manufacturers took part in one of the most unusual and colorful collaborations in their many antagonistic years together. Filled as their history was with street-front confrontations, often involving masses of picketing workers and violent weeks-long strikes, one has to imagine the scene to fully appreciate its novelty. In the otherwise staid setting of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union Dress Joint Board offices on West 40th Street, a stage was set up in June of 1941. Fifty-eight female contestants entered the office and made their way up the small flight of steps onto the stage. They were members of two local dressmakers unions and employees of various dress companies, there for a beauty pageant to determine which dress company employed the most beautiful female machine operators and finishers in the industry. John Powers, head of a local modeling agency, officiated at the pageant “with such swiftness of judgment that twenty-five were selected in the space of half an hour.” The twenty-five women would help launch the Dress Institute’s promotional campaign, thereby involving ILGWU members directly in an advertising effort for the industry, something that had never occurred before. Incidentally, with three contestants being chosen, the H. and H. Dress Company was the clear winner.

Indeed, relations between manufacturers and the garment union were so good that fifteen years went by in the industry without a strike, from 1933 to 1948. When the workers did strike again, it was not against garment manufacturers but rather against non-union

truck operators who tried to avoid unionization through intimidation and attacks on union organizers. But, increasingly, between the late 1940s and 1950, manufacturers were using low-skill, assembly line, non-union shops outside of New York City, where wage standards could not be enforced. The result was a rising number of mass production shops providing garments for cheaper wages. For the ILGWU, the uneven distribution of wage standards was an embarrassment to its authority. A mass walk-out was called, and some 65,000 workers across New York, Pennsylvania and New Jersey participated

peacefully, without pickets, merely to highlight the issue. Events came to a head when, in 1949, William Lurye, an ILGWU organizer, was killed by hitmen aligned with these non-union operators. On May 12, 1949, in a show of solidarity, some 65,000 union members marched again, this time to protest the killing.

Industry

Decline

Despite LaGuardia’s efforts to promote the city as a style center, the Garment District lost thousands of workers throughout the War years and beyond. The dress industry and the coat, suit and skirt industry took the biggest hits, losing nearly 22,000 workers between 1947 and 1956. By contrast, the counties immediately surrounding New York gained nearly 11,000 jobs in the same period, while Pennsylvania, Texas and the South became more important too.

What precipitated this decline? The 1950s witnessed one of the most important developments in the American fashion industry: the birth of modern sportswear. Capable of being freely mixed and matched by the consumer, sportswear – or separates – was the quintessential work of the contemporary American designer. Linked to more casual lifestyles that emerged as the American population moved out of cities like New York and into the suburbs, the creation of sportswear also set off the search for cheaper labor. Indeed, this fashion trend happened to coincide with the ILGWU’s political victories, most importantly, its control over wage scales, forcing upon manufacturers a new consideration: Why keep paying skilled tailors to do the unskilled work required for the sportswear boom? Cheap production sites where more space could be rented for less were close by, in places like Pennsylvania and New Jersey. In fact, standardized sportswear required more section work and, therefore, more space, usually a loft of at least 6,000 square feet. This was one fashion trend that did not match the limitations of a zoned Garment District, where space was at a premium.

The result was that many of New York’s smaller firms were left watching as their market share was eroded by garment centers that could turn out the volume of goods demanded by the sportswear consumer. Tragically, within ten years of the Garment District’s consolidation, its decline began. Moreover, the irony is that without a Garment District to promote as its own in the face of Paris’s demise, the industry may never have arrived at the creation of sportswear as a uniquely, quintessentially and self-consciously American fashion.

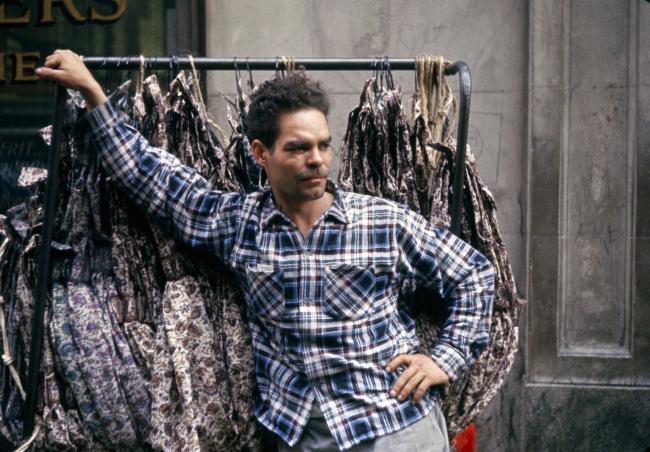

Manufacturers, increasingly dependent on section work, sought areas further and further beyond the union’s realm of influence. As the union eventually infiltrated those areas, entrepreneurs would simply move beyond the boundary line of control, in an ever-widening wave away from the city. This had devastating consequences for the district, particularly for those designers and manufacturers who chose to stick with haute couture. As they turned to their labor pool beginning in the 1960s, they found fewer and fewer of the specialized cutters, tailors and sewing machine operators they had relied on in the past. Not only were the unskilled jobs leaving the city, but skilled jobs were not being replenished when they needed to be.

Competition for the district continued, and not only from places like Pennsylvania and Texas. Instead, beginning in the 1960s, production sites such as Hong Kong, Seoul and Dhaka rose to prominence, fueled by the search for cheap labor. By 1980, imports accounted for half of all clothing in the country. Firms that could afford to compete adapted to changes in production by banding together to form conglomerates, resulting in the growth of large, multinational, publicly owned corporations that emerged from mergers between smaller firms.

Like their competitors, small firms that could not afford to move overseas began looking for cheaper costs. But where was cheap labor to be found? Jews and Italians had largely left the industry, and African-Americans and Puerto Ricans were not entering in sufficient numbers. Luckily, for some, this shift in the economic organization of the industry was accompanied by a resurgence of immigration to the United States.

Between 1966 and 1979, over one million legal immigrants entered New York alone, in addition to an untold number of illegal immigrants. As before, the garment industry became a central source of employment for the newly arrived. Between 1970 and 1980, the share of foreign-born Asians in New York’s garment industry quadrupled, while Hispanics from the Caribbean and Central America doubled their presence. The number of Asian-owned manufacturing firms also exploded, from around eight such shops in 1960 to four hundred thirty in 1980.

However, many of these shops were financed and controlled by the most powerful organized crime family in the country, the Gambinos, who maintained tight control over which manufacturers were linked to which of their mob-controlled sweatshops, going so far as to create direct and binding contracts between particular trucking companies, particular cutters and particular designers. For the Gambinos, the key to control over the garment district and industry was trucking. In fact, they consolidated their hold on trucking by creating a trucking trade association, the Master Truckmen of America (MTA). If a new company tried to break-in, soon all of its workers, unionized as part of ILGWU 102, would go on strike.

In fact, in 1969, the MTA and Local 102 threatened to bring the entire industry to a standstill by stopping all shipments in and out of the district. The threat was averted only when the city promised to “saturate” the area with police. If imposed strikes didn’t work, the Gambino family would use more direct tactics, such as taking up parking spaces or blocking curbs and sometimes entire blocks.

In fact, the roots of organized crime in the garment industry extend all the way back to the Uprising of the 20,000, in 1910. It was during the Uprising that labor racketeers first found their way into the industry. Paid by employers to break up strikes, the thugs and prostitutes who intimidated strikers were organized by gangsters.

One of the most notorious instances of union use of hired muscle was the gangster Dopey Benny, hired by the United Hebrew Trades from 1910-1914 to provide protection for workers and to ensure that the rights of Jewish workers were upheld. Dopey Benny was probably the first gangster to institutionalize the practice of racketeering, insinuating his men into ILGWU strikes to ensure the rank and file were not beaten from the picket lines by the thugs hired by manufacturers. Extremely well-organized, he divided the city into administrative districts for greater efficiency of service and even developed a price list for clients:

- Raiding and messing up a small plant: $150

- Raiding and messing up a large plant: $600

- Throwing a manager or foreman down an elevator shaft: $2,000

- Breaking a thumb or arm: $200

- Knocking out a person of “average importance”: $200

- Shooting a man in the leg or severing an ear: $60 to $600 (depending on the prestige of the victim)

Dopey Benny was eventually arrested and tried for attempted murder, bringing his reign to an end in 1914. His successor was Lepke Buchalter who ruled the district from 1927-1937. Like the Gambinos after him, he found that the key to controlling the Garment District was control over trucking. And like the Gambinos, Buchalter also took advantage of the economic disorganization of the industry: his rise to power coincided with one of the most difficult periods in the history of labor-management relations, when the ILGWU, emerging from a long “civil war,” was perhaps at its weakest point to date and easily exploited by manufacturers.

Indeed, the Gambinos and others before them were able to take advantage of a fundamental instability in the industry that exists still: involved in a finicky, seasonal trade, garment manufacturers often need cash quickly, and cannot always turn to banks on short notice; for example, when lines falter or a season is slow. Instead, some firms have turned to members of organized crime for loans, incurring high rates of interest as well as social indebtedness to the world of crime leaders.

Off-the-books financing has a long history in the garment industry as well, going back to the 26-week long strike that occurred as a result of the ILGWU’s civil war. Weakened by the strike and by the loss of business, which totaled millions of dollars, the industry desperately needed financing and turned to the underworld for help.

This is precisely what occurred in a resurgence of sweatshops that began in the 1960s and 1970s. Undercapitalized firms, facing financial ruin and overseas competition, turned to racketeers for loans. As a result, the Gambino’s ruled the district until the early 1990s, when the State Attorney General stepped in. As a result of a sting operation launched by the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office, the Gambino family’s role was exposed and their henchmen finally ousted from trucking within the district.

Manufacturing

Dwindles

But troubles for the district did not end there. Between 1958 and 1977, the number of garment manufacturing firms in Manhattan was cut in half, from 10,329 to 5,096. That trend would continue throughout the 1980s and 1990s: by 1996, the city had only 72,000 workers in the apparel industry overall, nearly half what the workforce had been in 1958.18 For the city as a whole, economic prospects were not particularly bright. By 1974, the city had incurred more than $10 billion in debt to cover past and contemporary budget deficits. Rather than try to bolster the manufacturing sector, the Mayor’s office chose instead to invest in the growing service sector. In the district alone, service jobs nearly doubled, changing the nature of the neighborhood and beginning a new competition for available space.

Competition came to a head in 1984, with The Times Square Development Plan, a $1.6 billion dollar proposal, offered by the city and the State Urban Development Corporation, to clean up the area around 42nd Street. The potential for more office encroachment on its territory alarmed the ILGWU and garment manufacturers. In fact, beginning in December of that year, the district saw the doubling of prices for floor space, from $8 per square foot to $16.

Special

Garment Center

Zoning

On November 9th of that same year, the Board of Estimate unanimously approved the plan to re-build Times Square. As part of its concessions towards the ILGWU and the industry, the city offered to study the possible effects of the plan on loft conversions in the district.21 The City Planning Commission also created the Special Garment Center District in 1987, whose purpose was to curtail loft conversion by using zoning to restrict some 8 million square feet of space to manufacturing uses. Almost immediately upon creation of the Special District, however, the city was sued by a consortium of real estate developers who felt that such zoning was not in keeping with the current needs of the city and placed an onerous burden on them. For four years the legal case dragged on, but the zoning measure was eventually upheld by a decision in 1990, signaling a victory for the ILGWU and garment manufacturers in their efforts to preserve the district.

It is ironic that the industry fought back, using the very tool that was given to it by its original opponents: the original zoning law of 1916, now deployed to keep non-manufacturing interests out rather than keeping garment work in, as was the original purpose in 1916.

The Fashion Center BID & the Fashion District Today

At the present time, the Garment District still grapples with how best to maintain a mix of manufacturing and office space. Debates about the efficacy and equity of the Special Garment Center District zoning continue, as does the decline of manufacturing due to competition from global labor markets. Today, the Fashion District, as the Garment District has come to be known, is still the home to the greatest names in American fashion. But new tenant groups have begun to fill the void left by manufacturers. In addition to marquee fashion designers, the Fashion District now also houses theaters, artists, architects, graphic designers, non-profits and commercial office tenants, which have, in turn, attracted new restaurants and retail tenants.

Spurring this development is the work of the Fashion Center Business Improvement District (BID), a non-profit public-private partnership formed in 1993 by Fashion District property owners. The BID model emerged in the 1980s as part of a wave of urban renewal that looked to the cooperative efforts of property owners to supplement municipal efforts in sanitation and public safety. The Fashion Center BID works with property owners, tenants and the City of New York on ongoing and specialized programs designed to promote the positive development of the district.

Through its public safety, sanitation and streetscape improvement programs, the Fashion Center BID works to create an appealing physical environment.

Its economic development programs are designed to help strengthen local businesses, while its tourism and promotion initiatives promote both the district and its tenants to customers, new tenants, brokers and the public at large.

In 1996, the Fashion Center BID launched its award-winning Fashion Center Information Kiosk. Located in the very heart of the district, on Seventh Avenue at 39th Street, the Information Kiosk provides a centralized site for industry information. Its unique architecture has also made it a beloved district icon.

In 2000, the BID also created the Fashion Walk of Fame®. Located along Seventh “Fashion” Avenue, the Fashion Walk of Fame honors notable American designers and is the only permanent monument to American Fashion anywhere in the world.

Today, several new hotels and residences are being built in the district or on its borders, and there are plans to develop the Hudson Yards on the Fashion District’s western flank. Accordingly, the Fashion District is sure to undergo significant change during the next several decades that will write the next chapter in the rich history of this enduring neighborhood. But, no matter what the future may hold for the development of the district, one thing is certain: the garment industry and district have played an important role in the history of New York

City and will forever hold a place in the hearts of its citizens. New York is a city of immigrants, and no industry or neighborhood has stronger ties to the people of New York City than the garment industry and its Fashion District.

The Fashion Walk of Fame honors the New York designers who have had a lasting impact on the way the world dresses.