Garment District

History Tour

Welcome to the Garment District!

The Garment District Alliance invites you to explore this authentic New York neighborhood. Learn about the area’s colorful history and unique architecture, and hear stories about the people, places and events that have made this the world-famous Garment District.

While you are in the neighborhood, be sure to visit www.garmentdistrict.nyc for restaurants, specialty shops and hotels, and to find out what’s happening in the district right now.

Protocols and Safety

Most building lobbies are open, but public access and photography are up to the discretion of the doormen, many of whom have worked in the same building for decades. Most are proud to share what they know about the neighborhood and may even allow photos if asked politely.

Be sure to look up, down and all around as you travel throughout the Garment District – there is a lot to see - but remember to be always mindful of vehicular, bicycle and pedestrian traffic!

Background

Planned and built, for the most part, in a little more than ten years, from 1919 to 1931, the Garment District covers 25 square blocks of Midtown Manhattan, from 34th Street to 41st Street, between Fifth and Ninth Avenues. Most of what you see around you was built to house what was once New York’s largest employer and most important industry: the design, manufacture and sale of clothing. In its heyday, New York’s garment industry employed more than 300,000 people.

Lower East Side Tenements

The story of this neighborhood starts about three miles south of the Garment District, on the Lower East Side. There, by the late 19th century, much of the nation’s clothing was being made by men, women, and children who worked long hours for low wages in poorly ventilated, overcrowded tenement apartments. Most were Jewish and Italian immigrants, who had little material wealth, but came to this country with something equally valuable: their skill as needleworkers and an entrepreneurial spirit.

Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire

By the early 20th century, New York State was cracking down on tenement sweatshops, and the industry began moving into commercial loft buildings, designed to house factories, showrooms and warehouses all under one roof. While better in some ways than cramped tenements, lofts could be equally dangerous. That became horrifyingly clear on the afternoon of March 25, 1911 when fire broke out at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory. Fire spread quickly across wooden floors, fueled by paper patterns and fabric scraps. As the workers — mostly female and some as young as 14 — tried to escape, they discovered that the doors were locked. Many were killed by smoke and flames; others died leaping to the pavement below. The city was in shock. On the official day of mourning, an estimated 100,000 marched and some 230,000 lined the streets to honor the fire’s 146 victims.

It was a tragedy that changed everything: the garment-industry labor movement went into high gear. Laws were enacted to radically change the design of manufacturing buildings and strengthen worker safety.

Industry Expansion

Meanwhile, the city exploded in size, and with it, the garment trade. Factories, with their tens of thousands of immigrant workers, edged uptown, encroaching on the fashionable department stores of Ladies Mile along Sixth Avenue in the 20s, and creeping ever closer to Fifth Avenue, which was becoming the city’s poshest shopping street. Merchants who ran upscale stores didn’t want their customers rubbing elbows with throngs of workers, who packed the sidewalks, smoking and gossiping on their breaks.

The New Garment Center

By 1916, garment-industry opponents had mounted a nasty campaign to move factories away from Fifth Avenue. A self-appointed “Save New York Committee” wanted to keep garment manufacturing below 34th Street, but the manufacturers had a better idea. They chose to build their new lofts on the site of the city’s former theater district, by then, a rundown working class residential and commercial area just north of 34th Street, between Broadway and Ninth Avenue. Known as the Tenderloin, the area’s cheap real estate made it attractive to developers, and it had the added advantage of being close to subway lines and Pennsylvania Station, which had opened in 1910.

The Garment District, much like you see it today, rapidly took shape. In 2009, its significance was officially recognized when it was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

The Big Button & The Garment Worker

555 Seventh Avenue

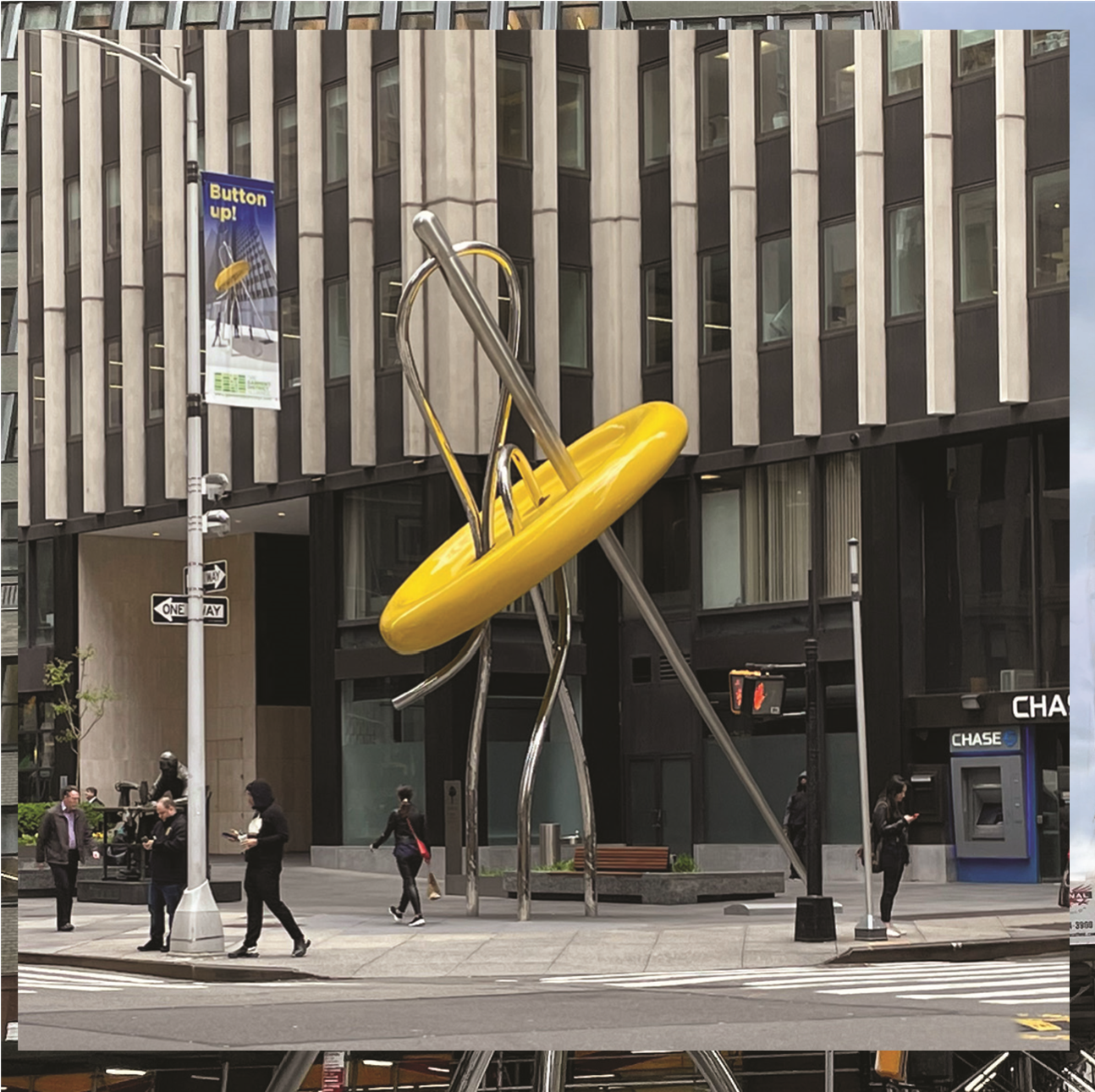

The Big Button

The Big Button is one of New York’s most recognizable public art works, a beloved neighborhood icon, and a social media crowd-pleaser.

Designed for the Garment District Alliance by Local Projects and Urban Art Projects (UAP), the Big Button creates a dynamic experience for locals and visitors. Supported by a stainless steel “thread” with a mirror-polished finish, the sculpture stands 28 feet tall, with a 15-foot wide aluminum button and a 32-foot brushed stainless-steel needle. Like the NYC taxi cab, the Big Button’s bright yellow color feels at home amid the hustle and bustle of Midtown, while the thread creates a sense of movement by reflecting the activity on our streets.

The sculpture you see today was unveiled in February 2023, but a Big Button has occupied this spot for decades. The original Big Button, designed by the architect James Beeber in 1996, was painted a fashionable black and sat atop an industry information kiosk that was operated by the Garment District Alliance. Twenty years later, personal mobile devices changed the way we access information, so the Alliance decided to remove the now-obsolete kiosk structure and enhance the Big Button by supporting it with a new magical thread element.

Although the intention was to reuse the original button, structural damage made it necessary to fabricate a new one, which led to this contemporary interpretation of the beloved classic. As the Garment District Alliance likes to say, “yellow is the new black!”

The Garment Worker

Nearby to the Big Button sits “The Garment Worker” statue, another significant public artwork that pays homage to the neighborhood’s history. In 1978, Israeli-born sculptor Judith Weller made a two-foot- high sculpture of her father, a Jewish tailor, working at a sewing machine which attracted the attention of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union. The union commissioned this eight-foot-tall bronze version, which was dedicated in 1984 and has graced this location ever since.